My Sponsor Comes to America

For the past year, I've been delighted to welcome Guinness as a sponsor on this blog--this week we learned we could welcome them back to the US as well:

Diageo today announced its intention to build a US version of Dublin’s popular Guinness Open Gate Brewery in Baltimore County, Maryland. As currently planned, the company would build a mid-sized Guinness brewery and a Guinness visitor experience with an innovation microbrewery at the company’s existing Relay, Maryland site. This new brewing capability and consumer experience, combined with a packaging and warehousing operation, would bring the company’s investment in Relay to approximately $50 million. The new brewery would be a home for new Guinness beers created for the US market, while the iconic Guinness Stouts will continue to be brewed at St. James’s Gate in Dublin, Ireland.This is not the first time Guinness has come to America, but the previous experiment ended after just six years. The current effort looks like a more ambitious and risky project. Diageo has been trying to figure out for years how to use the Guinness brand as an entry point into the craft market, with notably mixed success. The challenge for any giant brewery with such a strong brand presence is figuring out 1) how to expand without weakening the core product's position, while 2) convincingly appealing to customers in an entirely new segment. Most of the big breweries have concluded it can't be done, so they've followed AB InBev's strategy of just buying breweries in the craft segment. Can Diageo convince people that Guinness means both Irish stout and fullsome, tasty craft beer? Big gamble.

October Debuts

Speaking of arrivals, we have a new entry into the pretty-darn-crowded world of beer chatter.

Today, Pitchfork is proud to announce the launch of October, a digital publication focused on beer with an editorial perspective that speaks to a new generation of beer drinkers. A destination for devotees and novices alike to read about, learn about, and share their appreciation for beer and celebrate the culture around it. The site is being launched in partnership with ZX Ventures, AB InBev’s incubator and venture capital fund that focuses on increasing awareness and excitement around beer and brewing culture.The tie to ABI caused some sniping on social media, but the project is incredibly transparent. Read a little further and you learn that October is "overseen by Pitchfork’s creative studio and in collaboration with Michael Kiser of Good Beer Hunting, Eno Sarris of BeerGraphs." So far I don't see much that distinguishes the content from any other beer magazine. Kiser even has a think-piece up about where the Budweiser brand sits in the modern beer landscape, a perfect example of the way he brings insight and value to the conversation--while at the same time leaving that question of relationships with funders wide open. Still, the one knock I have on October so far is that it doesn't really seem to have a clear raison d’être that distinguishes it from, say Draft or All About Beer. Indeed, Good Beer Hunting seems to have carved out a clearer viewpoint.

New Branding

Two Oregon breweries sent me emails announcing new branding today, and they are both market improvements. I pass them along as an example of the way breweries are responding to a tightening market. In a world of jillions of brands, you can't have stale or bad packaging around. Rogue, which updates its flagship, had the former and Cascade the latter. Here's Dead Guy:

And the new Cascade.

Yeast and the New England IPA

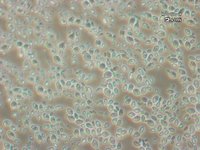

Finally, because I'm a completist, I want to direct you to the latest Beervana Podcast, and not just out of pure self-interest. Over the past year, we have discussed on these pages and elsewhere the nature of the New England IPA. Yesterday, Patrick and I paid a visit to the Imperial Yeast labs and did a pod with the three principals there. During the course of our interview, Owen Lingley discussed this beer style (they're getting a lot of questions about it from customers) and issued a rather bold, declarative position on the style as involves yeast. You will want to listen to hear his views--and learn all about yeast, which is a subject many of us wish we knew more about.

Happy weekend, you all--